Before movies and television, even before photos in newspapers, there were illustrated books that went beyond text to visually involve the reader. Sir Walter Scott’s stirring historical novels were clearly a prime candidate in this attempt to woo the eye with graphic images. However, including pictures with printed text was a technical challenge that was not adequately solved until the latter half of the nineteenth century. As books with illustrations became common, some publishers extended the concept to concentrate on the pictures. This example, published for the Royal Association for Promotion of the Fine Arts in Scotland in 1873, consists of six engravings by various artists coupled with brief extracts positioning them in the text of the novel. Publications like this, with large scale images printed on separate sheets, have often been broken up, framed, and displayed separately; thus losing the context in which they were originally presented. This volume is fortunately still intact.

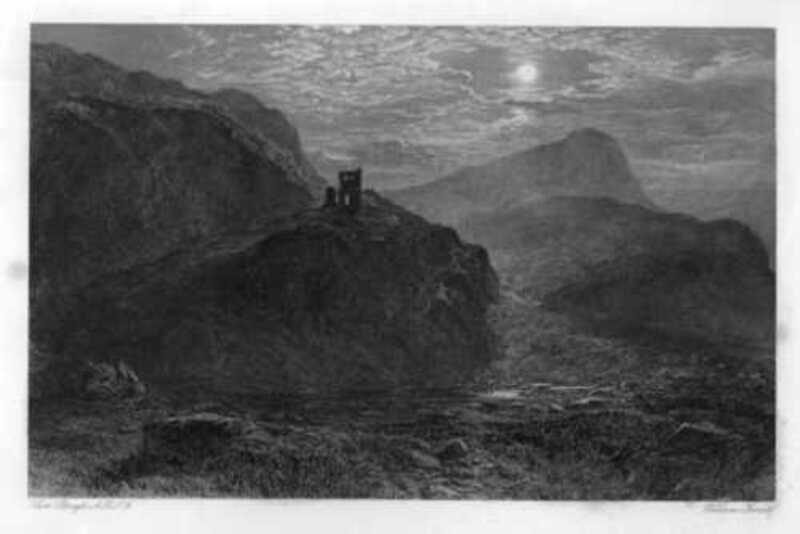

In this dramatic scene from Chapter 15 of Scott’s Heart of Midlothian (1818) the working-class heroine, Jeanie Deans, trying to save her sister from a charge of child murder, has overcome her fears to go to a moonlit meeting near the cursed spot of “Muschat’s Cairn.” The artist of the work is Samuel Bough (1822-1878), a self-taught Scotch landscape painter, who at the time this painting was completed was an Associate member of the Royal Scottish Academy. He was granted full membership two years later. Bough’s painting was transferred to a steel plate by engraver William Forrest (1805-1899), also a Scot, who had illustrated other books, including an edition of Scott’s Waverly Novels, during the Scottish literary boom of the first half of the nineteenth century. Steel engravings, such as this one, were often used to convert works from one medium, in this case a painting, to another for wider distribution. This illustration, rather poorly reproduced, appeared again in the 1898 “Border Edition” of the Waverly Novels, part of the University of Idaho’s Sir Walter Scott Collection.

Scott’s impact on the visual arts was more extensive than just illustrations of the novels. Ian Campbell has written that “the whole picture of what Scotland is, and was, came to be heavily derived from Scott&’s work.” This oversize volume of engravings was a part of that on-going process.

Written October 2001 for the UI Library’s Digital Memories website.

Sources

Scott PR5317.H4 1982