With the Lionel Hampton Jazz Festival approaching, we thought we would take a look at one of the investigations we did with our International Jazz Collections over the last year.

In 1996, Lionel Hampton was awarded the National Medal of Arts. This medal is awarded by the US government to artists and arts patrons who “…who are deserving of special recognition by reason of their outstanding contributions to the excellence, growth, support and availability of the arts in the United States.”1 At the time Lionel Hampton received the medal he had spent over 50 years performing as a musician and band leader. Beyond that he continuously advocated for music and jazz education for children throughout the country. In 1984, he performed at the University of Idaho Jazz Festival, which he became a great benefactor of and for which the festival was re-name in 1985.

When the University of Idaho received the Lionel Hampton papers in the 1990s, included were a vast number of Hampton’s awards and achievements, including the National Medal of Arts. In preparing for 2020 festival, we pulled the medal and noticed some concerning discoloration.

Unfortunately, no one on our small team is a conservator, so we began researching to try and find out exactly what was happening to the medal. First we tried to find out what the composition of the medal. Was it gold? Bronze? Nickel plated? We couldn’t find any information online about what the contents of the National Medal of Arts. We even tried calling the National Endowment of Arts office to see if they had information, and they didn’t know what to do with our request.

With our avenues of information becoming more and more slim we turned to the great and wonderful conservators of the world, posting an inquiry on the Global Conservation Forum’s listserv with some pictures of the medal, a description of the discoloration, and a cry for help. Had anyone seen this discoloration before? And if so, did they know what to do?

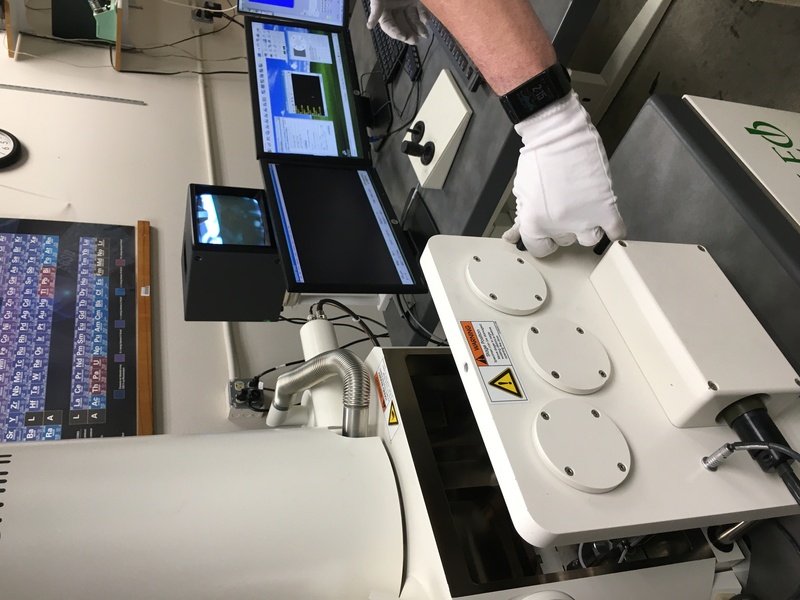

The response was heartening, we received a lot of great and wonderful advice, but we still could not say for sure what the medal was made of. One conservator thought it looked like it was caste bronze, another believed it to be gold plated nickel, and there were some other guesses. It was suggested that since our collection was at a university that the university might have a Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) that could be used to determine the composition of the medal. An SEM is a type of electron microscope that scans materials by focusing a beam of electrons at the material, scanning the sample and producing an image. Another ability of the SEM is to help identify chemical compositions of what is being scanned.2

It turns out our university’s Department of Geological Sciences did have an SEM, so we began looking into options of having the medal scanned. And one February day last year, a staff member and the medal made the trip across campus to learn about the National Medal of Arts on a molecular level.

After the scans were complete, and our data was collected, we still needed for it to be interpreted. So, we sent it to the conservator who suggested the scan in hopes he could tell us the composition of the medal. According to him, it appears that the medal was silver at it’s base with subsequent layers of copper, nickel, and gold (a standard way of gold-plating silver). The copper and nickel layers are used to help adhere the gold layer to the silver. Based on this, we determined that the nickel layer was corroding.

Since it’s discovery, we have attempted to address any issues that could exasperate the issue by rehousing the medal and removing it from anything that could have added to the corrosion.

Throughout this process we were able to ascertain with reasonable certainty the composition of the National Medal of Arts. Unfortunately, we do not know what caused the corrosion initially. We do not know if it was there when received it. We do not know if something happened under our care. Moving forward, however, we have documented what was happening, discovered the chemical composition we are dealing with, rehoused the medal, and are better prepared to care for it going into the future.

We hope that our journey of discovery may help others who find a corroding National Medal of Arts in their collection.

![Discoloration of National Medal of Arts-front [1]](https://objects.lib.uidaho.edu/harvester/small/hamptonnationalmedal-06_sm.jpg)

![SEM Scan of National Medal of Arts [4]](https://objects.lib.uidaho.edu/harvester/small/hamptonnationalmedal-04_sm.jpg)

![SEM Scan of National Medal of Arts [1]](https://objects.lib.uidaho.edu/harvester/small/hamptonnationalmedal-01_sm.jpg)

![SEM Scan of National Medal of Arts [2]](https://objects.lib.uidaho.edu/harvester/small/hamptonnationalmedal-02_sm.jpg)