Post written by Brian Tibayan, 2024 Gary E. and Carolyn J. Strong Fellow.

For over 50 years, the WWAMI (Washington, Wyoming, Alaska, Montana, and Idaho) Program has been a beacon of innovation in medical education, improving healthcare delivery through quality physician training. Established to address the healthcare crisis in rural and underserved areas, students complete their first year of medical school in the five states before continuing at the University of Washington. WWAMI addresses physician shortages by increasing the number of primary care physicians and improving healthcare provider distribution. Students are trained to be proficient in clinical skills and patient care through rigorous coursework and hands-on training (Schwarz, 2014). Medical simulations are a key part of WWAMI’s training curriculum, enhancing students’ practical experience both clinically and in patient care. As a simulated participant (SP) for WWAMI, I have played the role of a patient in simulations that help students improve their clinical and communication skills. Through this role, I have witnessed firsthand the importance of empathy and communication in simulations and their profound impact on preparing future healthcare providers.

Patient Care Then and Now

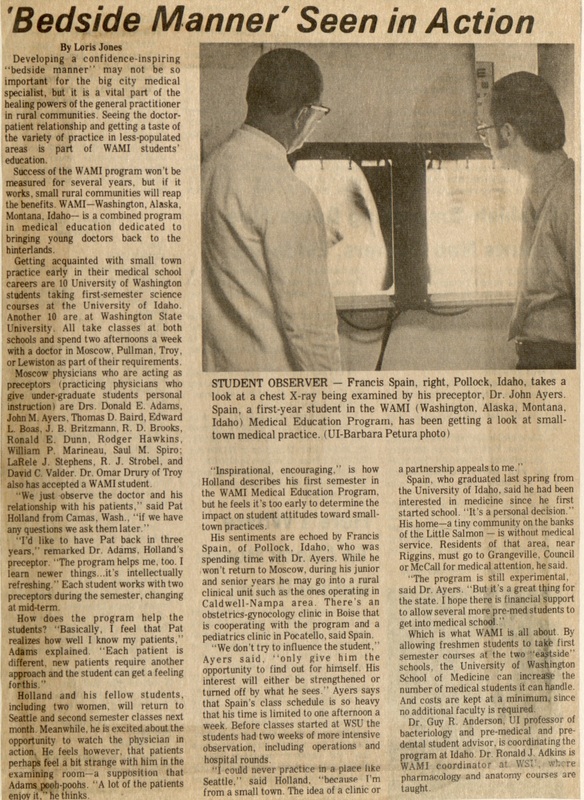

Patient care is an integral aspect of medical training. Historical records have shown the importance of relationship-building in medical practice. Exploring the WWAMI archives, I discovered three articles that stress the relational aspects of medical education: Bedside manners, training with volunteers, and patient attitudes towards doctors. These articles, though decades old, resonate deeply with my current doctoral research, stressing the timeless importance of empathy, in this case, on patient care and hands-on medical training. A 1972 article entitled, “Bedside Manner Seen in Action,” vividly captured the essence of developing a confidence-inspiring, doctor-patient rapport. Medical students back then learned by closely observing seasoned physicians and engaging directly with patients. This hands-on approach was not just about medical procedures but about connecting with patients on a human level, building trust, and equipping future doctors to provide compassionate, effective care (Jones, 1972). Similarly, another article delved into the innovative techniques used to teach medical students about patient attitudes. Through patient interviews and interactive lectures, students were encouraged to see patients as individuals with unique stories and needs, rather than just cases to be solved. This approach was particularly impactful when it came to understanding the perspectives of elderly patients.

As the program evolved, simulations became a key component in medical training, as seen in an article showcasing male volunteers as demonstration patients for sensitive examinations. These simulations were essential. Students learned to handle intimate clinical procedures with professionalism, overcoming their own personal discomfort. More importantly, students learned the value of sensitivity, care, and respect for patient privacy and dignity. Additionally, the training included discussions on medical ethics and the physician-to-patient relationship (“Future Med Students Prepare with Male Volunteer Patients,” 1988).

Today, WWAMI continues to use simulations extensively in medical training. Medical students engage in realistic scenarios that mimic actual patient interactions, allowing them to apply their clinical knowledge in a practical setting. These simulations are also critical in cultivating strong patient-doctor relationships. Students can understand their strengths and areas for improvement better because of the structured real-time feedback from SPs. Through repeated practice, students learn to communicate more effectively, build trust, and demonstrate empathy, which are all essential skills in patient care. Overall, medical simulations make learning more meaningful, immersive, and impactful.

The Role of Empathic Communication and Improvisation in Medical Simulations

Historical insights from the WWAMI collection at the University of Idaho illuminate the vital role of empathy and improvisation in medical training. Being present, thinking clearly and quickly, and connecting with patients with respect and sensitivity demonstrate empathy and improvisation in action. Communicating with empathy means truly understanding and sharing the feelings of others. Medical students learn to adapt and tailor their communication style to create a supportive and trusting environment for patients. Studies have shown that empathy in communication leads to better patient outcomes, higher satisfaction rates, and improved adherence to treatment plans (Del Canale et al., 2012; Riess, 2017). As a simulated participant, I recognize the profound influence of empathy and clear communication in simulations. When medical students listened actively, acknowledging my concerns and emotions, I felt genuinely cared for and understood. As trust was established, I felt more inclined to follow the medical advice given and was satisfied with the interaction. By delivering medical information sensitively and addressing my emotional needs, they made complex concepts more understandable and less intimidating. Thus, communicating with empathy can reduce patient anxiety and create a supportive environment where patients can feel comfortable discussing sensitive health issues. Improvisation, defined as responding spontaneously and intuitively to the present moment (Spolin, 1999), is another invaluable tool in medical simulations. Improvisation helps students quickly adapt to scenarios, enhancing their ability to communicate effectively, think on their feet, and provide compassionate care. The beauty of improvisation lies in its capacity for continuous improvement. If one approach doesn’t work, students can try another method under the guidance of faculty coaches and colleagues. In my experience, students who engage in improvisation noticeably improve their ability to handle complex scenarios with more confidence. These simulations provide a safe environment for practicing and refining such skills, preparing students for real-life medical situations.

Takeaways

WWAMI has consistently prioritized comprehensive training for medical students. The historical context of medical training and its evolution to modern practices demonstrate the enduring importance of improvisation and empathic communication integrated in medical simulation. These methods have been known to improve patient care and better prepare medical professionals. By incorporating patient-centered approaches and evidence-based simulation techniques, WWAMI creates a robust training environment that nurtures both clinical and communication skills. These practices not only prepare students for the technical demands of their profession but also equip them with the interpersonal skills necessary to build strong and meaningful patient relationships. As WWAMI continues to innovate and adapt, the program remains a vital force in shaping compassionate, competent healthcare providers who are well-prepared to meet the challenges of today’s medical landscape.

References

Del Canale, S., Louis, D. Z., Maio, V., Wang, X., Rossi, G., Hojat, M., & Gonnella, J. S. (2012).

The relationship between physician empathy and disease complications: An empirical study of primary care physicians and their diabetic patients in Parma, Italy. Academic Medicine, 87(9), 1243-1249.

Future med students prepare with male volunteer patients. (1988, October 3). The Daily Evergreen.

Jones, L. (1972, December 5). Bedside manner seen in action. The Daily Idahonian.

Medical students interview for patient attitudes. (1977, April 29). Argonaut.

Riess, H. (2017). The impact of clinical empathy on patients and clinicians: Understanding empathy’s side effects. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 32(5), 624-627.

Schwarz, M. R. (2014). WAMI: A bold beginning, an experiment in medical education (1st ed.) [Unpublished manuscript]

Spolin, V. (1999). Improvisation for the Theater. Northwestern University Press.