Two hundred years ago, when the pace of communication and publication was slower than today we would think that by the time news gets encapsulated in book format all the errors have been corrected. If newspapers are history’s first draft, then the subsequent books provide the opportunity for substantial revisions and corrections in that draft.

Pubic interest in the Lewis and Clark Expedition was fostered in newspapers of the time by brief accounts reporting on their departure, their return, and the planned publication of their report. Unfortunately, the report was delayed by circumstances, chief among them Lewis’ untimely death at Grinder’s Inn on the Natchez Trace. Into this information vacuum stepped several authors, compilers, and publishers, eager to monetize the public’s desire for information about the newly acquired vast western lands.

Beginning in 1809, a variety of authors and publishers contributed to this tributary branch of the Lewis and Clark literature. These many editions borrowed heavily from previously published reports and threw in a vast amount of completely irrelevant material. Scholars consider these spurious or apocryphal accounts of Lewis and Clark journals. Surprisingly, these publications continued after the 1814 “official” publication of the Biddle and Allen History of the Expedition.

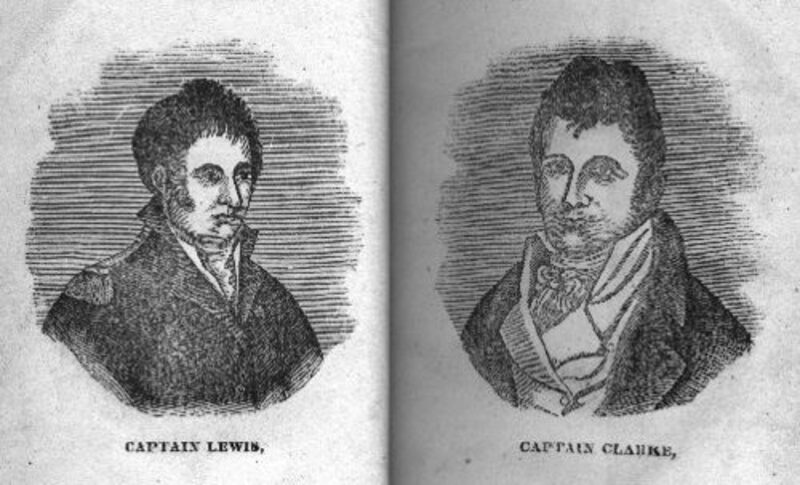

Even as late as 1840, a frontier printer in Dayton, Ohio, B.F. Ells published a small volume entitled The journal of Lewis and Clarke to the mouth of the Columbia River beyond the Rocky Mountains in the years 1804-5, & 6: giving a faithful description of the river Missouri and its source - of the various tribes of Indians through which they passed - manners and customs - soil - climate -commerce - gold and silver mines - animal and vegetable productions, & c. In spite of the lengthy title, this is little more than a slightly revised version of an 1813 Baltimore imprint with new errors added. It includes President Jefferson’s two messages to Congress, a preface containing a statistical summary of the value of the Missouri fur trade and two lead mines, William Clark’s letter to Gov. W. H. Harrison from Fort Mandan, and to his brother on his return to St. Louis, a great deal of (mis)information about Indian culture, an extract from William Dunbar’s survey of the Red River, a “dictionaty” of Indian words and phrases, and an appendix with accounts of President Washington’s offer to provide college educations to some “Chypewyan” Indians, an French military excursion against the “Sawkees,” a story of an Indian nurse, and, even more inappropriately, an account of an African snake killed by the Roman general Regulus. The portraits of Lewis and Clark prepared for the frontispiece were re-engraved and simplified.

Among the falsehoods presented as fact is the statement that the Corps of Discovery threatened the unruly Sioux with a smallpox infection. “We received authentic intelligence, that the Sioux had it in contemplation (if their threats were true) to murder us in the spring; but were prevented from making the attack, by our threatening to spread the small pox with all its horrors among them.” Dr. Chuinard, in his authoritative Only One Man Died: The Medical Aspects of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (1979) recounts this tale and noted “This appears to be entirely a fabrication.” The source of the fabrication has not been determined.

That the work would find an audience at this late date also suggests that the lack of communication between the frontier and the eastern cities encouraged the reprint of a spurious edition instead of the official account, which Harper & Brothers reprinted in 1842. First, there were probably few copies of the History of the Expedition available to make comparisons. Second, copyright, though poorly enforced and implemented, may have kept Ells from undertaking a reprint of an official document. And third, he may have only had at hand the 1813 apocryphal edition and felt that none would be the wiser if he published it instead of the original.

For more information about this genre of spurious publications, and other Lewis and Clark items, see The Literature of the Lewis and Clark Expedition: a Bibliography and Essays (Portland: Lewis and Clark College, 2003).

Written July 2003 for the UI Library’s Digital Memories website.

Sources

Day-NW Oversize F592.7.B43 2003