In early June 2024, I had the opportunity to meet the people who run 12 cultural heritage institutions across North Idaho and interview them about their collections, their challenges and personal history in preservation work. The survey had three purposes; to establish connections with cultural institutions, identify cultural gaps within our own digital collections and explore how our university could highlight selections from these archives without formally accessioning the items into our own special collections.

As the Digital Initiatives Librarian in the Digital Scholarship and Open Strategies (DSOS) department, this was a somewhat unconventional survey for me to work on. Physical collections are usually the focus of our archivists, with my work focusing primarily on using static web design to create and maintain digitized versions of archive items that have already been processed, arranged and cataloged by the Special Collections department. That said, there have been developments within our library that have allowed us to look beyond this more conventional model of digital initiatives.

The approachability of our open source framework CollectionBuilder, which we use to create all of our collections at U of I, has allowed archivists to create their own digital collections without assistance, such as the recent Silver and Gold Book and Earl Bennett Stock Certificates collections. Alternately, DSOS has also experimented with creating digital collections without formally accessioning items, either scanning here in Moscow and returning documents, in the case of the Taylor Wilderness Research Station Archive, or receiving the digital surrogates of the items and their corresponding metadata completely remotely, as we are doing with the ongoing Potlatch Historical Society Collection. The latter approach has interesting potential for small community archives, highlighting their important preservation work and promoting underrepresented regional history while allowing these archives to retain stewardship of their materials and keep the items in their communities.

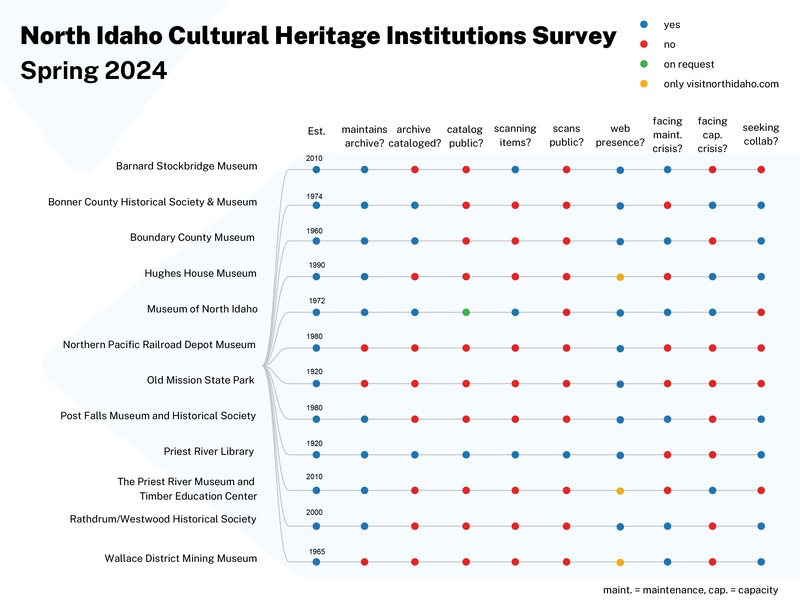

The “cultural heritage institutions” I grouped together for this survey consisted of museums, historical societies, a library and a site maintained by the National Parks Service. The names and functions of these institutions often overlapped, with historical societies sometimes creating public facing museums and museums sometimes maintaining archives of items they hope to one day digitize or simply don’t have display space for. Seventy five percent of these institutions maintain some form of archive, using the Society of American Archivists definition of “records created or received by a person, family, or organization and preserved because of their continuing value.” That said, what these archives looked like and how they functioned varied dramatically, ranging from traditional layouts to backroom bookshelves, obscured closets and offsite storage.

Nearly a third of these archives are engaging in some sort of cataloging, often utilizing digital asset manager PastPerfect, in surprisingly extensive, decades-long running programs. I found only a few institutions taking the further step to digitize their materials and none making these scans completely open access, with entities such as The Museum of North Idaho in Coeur d’Alene watermarking these digital surrogates on their public facing catalog and selling the unaltered digital files as an element of their financial structure.

In my interviews, I also wanted to explore the day to day obstacles as well as the existential threats to better understand their preservation challenges. An overwhelming theme began to emerge around institutions being unable to resolve relatively straightforward maintenance issues due to complicated ownership status of their buildings. Often, these sites are donated or charged very low rent by churches, government or philanthropists, allowing these non-profits to function but not maintaining the spaces and sometimes contractually restricting them from making necessary structural improvements or adding extensions to the property.

Of the 12 sites I visited:

- Half are facing imminent structural crisis, predominantly due to damaged roof structures, water damage and mold

- One third are also facing a capacity crisis and unable to build auxiliary storage space due to zoning or ownership status

- Nearly half of the sites have inherent accessibility issues stemming from occupying historic buildings

While I also recorded anxiety around aging volunteers, staff and board members as well as frustration about lack of support at municipal, county and state levels, I found these institutions succeeding despite these conditions, buoyed by fulfilling a unique function within their communities as regional memory centers. Examples include providing an archival reading room within a museum space like the Boundary County Museum, producing regular newspaper and radio content utilizing archival materials like the Bonner County Historical Society as well as trailblazing community service and environmental cleanup efforts that are an extension of the Priest River Museum. I hope this survey has not only illuminated worthwhile future partnerships for U of I but also helps these institutions recognize the similarity of their challenges and encourage both dialogue and organization towards a shared vision of preservation for Idaho’s cultural heritage.

Sincere thanks for your participation to:

- Tammy Copelan, Barnard Stockbridge Museum

- Hannah Combs, Bonner County Historical Society & Museum

- Sue Kemmis, Boundary County Museum

- Jeanne Johnson, Hughes House Museum

- Dorothy Dahlgren, Museum of North Idaho

- Kathy, Northern Pacific Railroad Depot Museum

- Will Niska, Old Mission State Park

- Catherine McClinktick and Kim Brown, Post Falls Museum and Historical Society

- Christa Shanaman, Priest River Library

- Carl Wright, The Priest River Museum and Timber Education Center

- Lisa Peterson, Rathdrum/Westwood Historical Society

- Dr. Dick Vester, Wallace District Mining Museum