Post written by Brian Tibayan, 2024 Gary E. and Carolyn J. Strong Fellow.

Throughout my Ph.D. journey, my fascination with the qualitative nuances of research has guided my academic pursuits. I constantly look for patterns, themes, and the interconnectedness of these elements. This skill set has profoundly shaped my academic journey, allowing me to dive deep into the complexities of research and diverse narratives. This year, I had the incredible opportunity to serve as the Gary E. and Carolyn J. Strong Special Collections Fellow, an experience that has been both enriching and rewarding.

My background in qualitative research prepared me well for the fellowship, where attention to detail and analytical thinking are crucial. This role allowed me to apply my academic knowledge and experience in a practical setting, particularly with the WWAMI (Washington, Wyoming, Alaska, Montana, and Idaho) collection. WWAMI is a collaborative medical education program, involving the states of Washington, Wyoming, Alaska, Montana, and Idaho, designed to train physicians and improve healthcare access in these regions.

Having worked as a Simulated Participant (SP) for WWAMI, I was excited to delve into its archives and learn more about the program, especially its early years. SPs, also known as standardized patients, are performers trained to act specific roles in controlled settings for educational or training purposes. In WWAMI’s case, SPs play the role of the patient to provide students with hands-on experience, testing their medical knowledge and communication skills in patient interactions. These roles are critical for creating immersive learning experiences that enhance the practical skills of learners in various disciplines. My dual experience as a Simulated Participant and a Strong Fellow working on the WWAMI archives provided a unique and profound understanding of the program’s impact, both historically and in practice.

Working with Special Collections

Stepping into the Special Collections and Archives Department at the University of Idaho Library was both thrilling and daunting. Initially, the vastness of the collection and the meticulous work required to manage it shaped my impressions. Over time, these feelings quickly evolved as I became more involved in the project, guided by the supportive staff. Dulce, Kelley, Ariana, and Sara played a crucial role in my acclimation. They each provided guidance and encouragement that helped transform my initial thoughts into confidence and enthusiasm for the work.

The WWAMI collection is a rich repository of educational and historical materials. This collection includes a variety of documents, photographs, and other artifacts that span several decades, reflecting the program’s impact on medical education and community health. My first task was to thoroughly sort, consolidate, and organize the collection, starting with six file boxes and three scrapbook boxes. Personally, the fun part was identifying documents and materials that belong together, and discovering patterns and themes that create cohesive groups. I eventually reorganized the collection into nine categories or series: Financial Records (1972-1989); Courses (1980-1989); Students (1972-1989); Faculty (1979-1989); Administrative/Office (1972-1990); Committee Meetings, Minutes, and Reports (1984-1990); Events, Programs, and Projects (1984-1989); Photographs (1972-2016); and Scrapbooks (1946-1997). For a more detailed list of of materials in the collection, please visit the WWAMI records finding aid.

I also digitized a scrapbook that captured the early days of WWAMI, from its inception to the introductory years of the program. Digitization preserves original items by reducing physical handling and makes the collection more accessible to a wider audience through easily shareable and viewable digital files. The chosen scrapbook includes black-and-white photographs of meetings and field trips, as well as letters discussing program approvals, recommendations, and resolutions. Newspaper clippings chronicle both praise and criticism of the WWAMI program, its initiatives to address rural medical shortages, and the involvement of local physicians. Press releases and photographs document significant milestones such as the arrival of the first University of Washington medical students at the University of Idaho and tours of rural clinics. In general, the WWAMI collection provides a comprehensive overview of the program’s development and achievements. This collection not only preserves the historical significance of WWAMI but also serves as a valuable resource for research and education. You can view the WWAMI Scrapbook digital collection here: WWAMI Scrapbook.

Another crucial aspect of archival work is metadata creation. Creating metadata for the collection is essential for making the materials accessible to researchers because it provides structured and searchable information about each item. Metadata includes descriptions, keywords, dates, and other relevant details that help researchers quickly find and understand the context and significance of the materials. Without detailed metadata, navigating large collections can be time-consuming and difficult, and researchers can potentially overlook valuable resources. Metadata ensures that the collection is organized, user-friendly, and maximizes its research potential. The metadata is then integrated into the online database to allow researchers to search and access the materials remotely.

Archival Work Yields New Leads

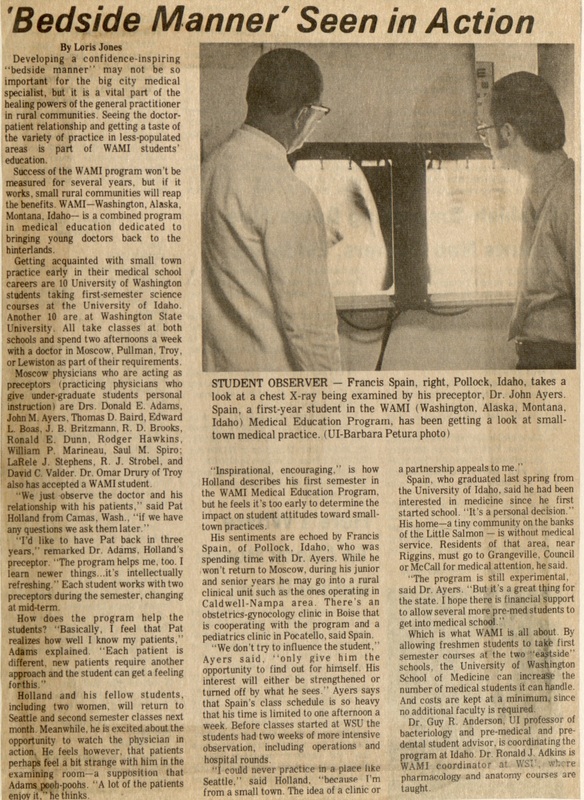

Having examined the collection, I was determined not only to write about my archiving experience but also find deeper connections that explain why this kind of work is important. In my research, I came across articles discussing the “bedside manner” of student doctors, the use of volunteer patients for simulation, and patient attitudes towards doctors. Given my involvement in WWAMI, I wanted to investigate the importance of empathic communication in patient care training, if this was an approach that WWAMI considered during its early years.

Inspired by my curiosity and keen interest in uncovering new knowledge, I decided to conduct further research at the Special Collections of the University of Washington Library. This visit provided another great opportunity to observe and learn about archival practices at a different institution. My time at the University of Washington (UW) Special Collections was pivotal in broadening my understanding of archival work. I had the chance to see how UW manages their collections and the strategies they use to maintain their archives. Additionally, since UW serves as the administrative hub for the WWAMI program, the Special Collections at UW holds more resources about the program’s history and development.

On the day of my visit, I was greeted by the impressive Gothic architecture of the Suzzallo Library at UW. Its entire structure was replete with ornate details of intricate stone carvings, spires, and decorative motifs. Inside, the library boasted high vaulted ceilings and beautiful stained-glass windows that allow natural light to filter in, creating a majestic atmosphere. I thought to myself, “If the sheer scale of this library was any indication of their archive collection, I’m in for a treat.” True to form, their Special Collections did not disappoint.

Connected to the Suzzallo Library is the Allen Library, where Special Collections is located. Both libraries had distinct architectural styles, one Gothic and the latter more modern but still equally impressive. The UW Special Collections is situated in the basement level. Arriving at the lobby, I notice their featured exhibit titled “Breaking Bread: Foodways and Cuisine in Print,” which explored the cultural, historical, and artistic aspects of food and cuisine as represented in printed materials.

Entering Special Collections, I immediately noticed the spacious and well-lit exhibition area featuring a variety of display cases filled with historical and educational materials. This exhibit prominently titled “The Medium is the Message” invites visitors to explore the impact of different mediums on storytelling and historical narratives. Display cases contain a mix of graphic novels, books, and related artifacts that emphasize how lived experiences and personal stories are conveyed through visual and textual mediums.

Allee Monheim, the Special Collections public service librarian, assisted me with the pre-requested WWAMI collections. I felt a surge of excitement and anticipation as I went through four boxes of WWAMI files from the ’70s and a comprehensive manuscript by one of the WWAMI founders, Dr. M. Roy Schwarz. Who knows what hidden gems one can find in this treasure trove of information? I practically stayed in the library the whole day, thoroughly engrossed in all the materials.

An Archivist’s Perspective

One of the highlights of my trip was interviewing archivist, John Bolcer, who has dedicated his 27-year career to managing and preserving the vast array of materials within Special Collections. During our conversation, he shared insights into the challenges, strategies, and significance of archival work in higher education institutions. The importance of meticulous record-keeping and preservation cannot be overstated.

Over the years, the field of archiving has transformed significantly, particularly in processing and describing collections. John recalls that archivists initially employed detailed item-level descriptions, painstakingly cataloging each document, which was time-consuming and often led to backlogs. However, as collections grew and the demand for access increased, archivists shifted towards more streamlined approaches. Bolcer states:

In the past, we spent a lot of time on item-level descriptions, but as collections grew larger, this became impractical. Now, we focus more on collection-level descriptions––what archival theorists Mark Greene and Dennis Meissner called ‘more product, less process.’

This shift allows archivists to process collections more efficiently, making them available to researchers more quickly while maintaining the overall context and significance of the materials.

A key theme in my interview with John was the importance of provenance—the record of ownership and understanding the context of archival materials. “Provenance is central to understanding records,” John asserted. “It’s not just about the item itself but about who created it, why, and in what context.” This principle guides Special Collections in categorizing and interpreting their holdings. He described the archives’ focus on maintaining the integrity of collections by preserving the original order and context of materials. “It helps researchers piece together the full story, rather than just isolated facts,” he noted. Knowing the background and circumstances of a document’s creation is crucial for proper interpretation in archival work, ensuring that the records are not misinterpreted or taken out of context.

As I looked around the room, I wondered what a challenge it must be to maintain consistency across such diverse collections, especially with an extensive repository that is over 60,000 cubic feet. John acknowledged the difficulties arising from divided curatorial responsibilities and varied approaches. He asserted the importance of coordination, stating, “We have to ensure consistency in processing and linking collections, especially when materials are acquired from different sources.” This necessity for collaboration across departments requires a nuanced appreciation of both the materials and their potential research value. Bolcer provided a practical example to illustrate how this coordination is achieved:

If we acquire a collection that includes photographs, manuscripts, and audiovisual materials, those might fall under different curatorial units. We must work together to ensure that the collection is processed in a way that makes sense as a whole, rather than treating each type of material in isolation.

This approach affirms the critical role of cross-departmental collaboration in archival work and the need for consistency in processing and linking collections, especially when materials are acquired from different sources.

Staff attrition and the sheer volume of materials are ongoing challenges for Special Collections. John addressed this by mapping staff to functions effectively, ensuring that newer staff gain access to the knowledge held by long-tenured employees while keeping the latter updated with current practices. The reliance on student employees and graduate students, who often work for only a couple of years, further complicates this balance.

After spending a full day at UW’s Special Collections, I asked John what he thought about the importance of continuing this gargantuan task despite the challenges. After all, the role of archival work in preserving institutional memory and historical records is indispensable. John stated:

Archives validate identity, preserve memory, and enable rediscovery. It’s not just about keeping old documents. It’s about understanding the context in which they were created and why they are significant. This helps prevent historical revisionism and ensures a more accurate account of past events.

Moreover, John offered invaluable advice for future and new archivists entering the field:

Stay curious and adaptable. The field of archival work is constantly evolving, and new technologies and methods are always emerging. It’s important to stay up to date with these changes and to be willing to learn and adapt. Building strong relationships with colleagues and researchers is also crucial, as collaboration and networking can open new opportunities and insights.

John’s forward-thinking approach vividly illustrates the dynamic nature of archival work, demonstrating its crucial role in preserving our collective history and paving the way for future discoveries. By continuously adapting and embracing new methodologies, archival work not only safeguards our past but also enriches our understanding and opens new avenues for research and insight.

Lessons Learned

Reflecting on my journey as this year’s Strong Fellow, I rekindled my love for history. Winston Churchill once said, “Those that fail to learn from history are doomed to repeat it.” This adage holds especially relevant in today’s overwhelming age of information, emphasizing the critical role of archives in preserving history. My experience has deepened my appreciation for the incredible work in archiving and its significance in safeguarding our collective memory. Through this journey, I have realized the profound impact of preserving our collective memory. My time with Special Collections and Archives at the University of Idaho has been truly transformative. Learning archival methodologies and navigating extensive collections has deepened my appreciation for the vital work of archivists. Overall, these experiences have equipped me with the essential tools for future scholarship and preservation efforts.