Post written by Jack Kredell, inaugural recipient of the Lynn and Dennis Baird Fellowship.

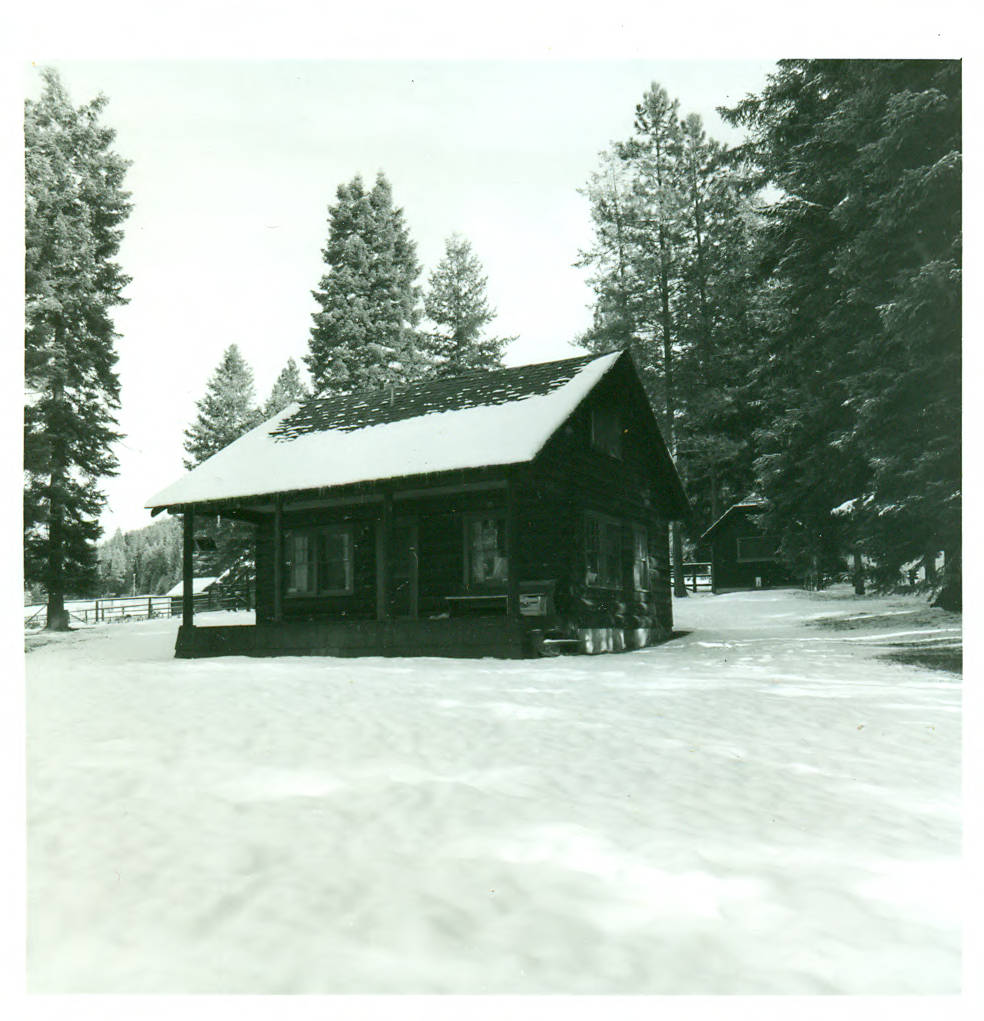

Richard A. Kuhl (1938-2019) spent the better part of a decade working as a wilderness ranger at the Moose Creek Ranger Station, a remote Forest Service field station and airstrip located in the heart of the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness.

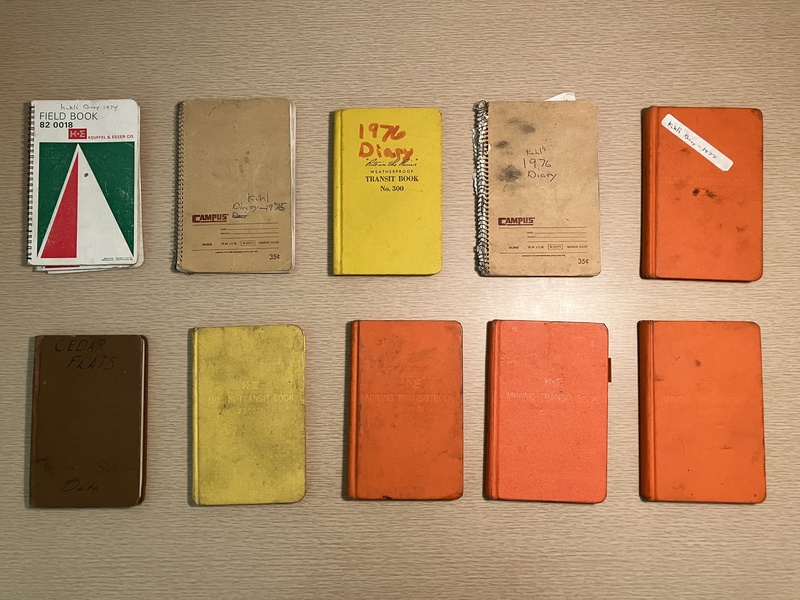

Spanning the 1974-1981 seasons (roughly late spring to fall each year) and available for viewing in the University of Idaho’s Library Special Collections & Archives, Kuhl’s field notebooks offer a unique glimpse into the daily life of a wilderness ranger. They tell the story of an individual whose ability to hike long distances was matched only by his patience— skills that proved essential in his job of enforcing the rules and responsibilities of a wilderness ethic that, in those early days at least, had not yet been fully adopted by the area’s recreationalists. The notebooks also hint at a more complicated story—one told through leavings and traces—about the relationship between human presence and Wilderness.

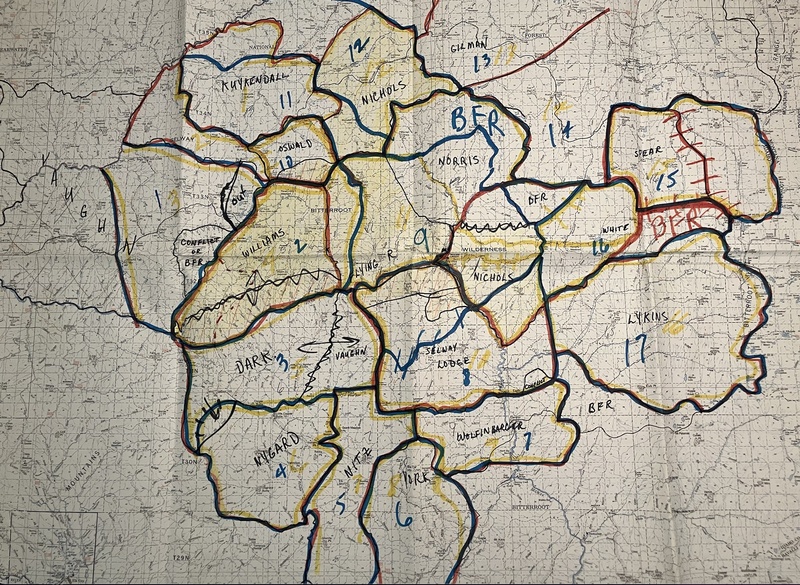

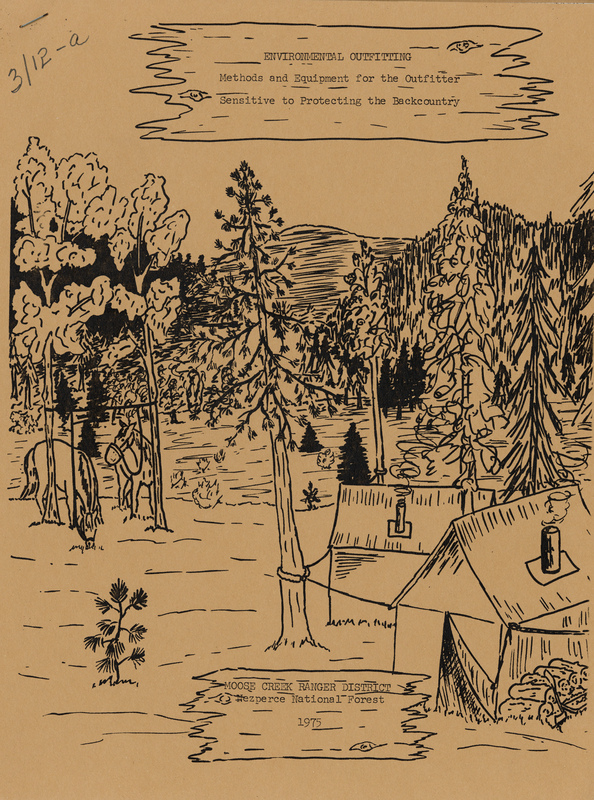

On July 22nd, 1980, Kuhl hiked from Fish Lake to McConnell Mountain, a distance of roughly 9 miles, to do a day’s worth of trail work and inspect a nearby hunting outfitter’s camp. Kuhl found “camp a mess. Tent pegs in ground, cig butts and food…grill, saw and axe beside trail, 2 charcoal heaps, rock fireplace, poles upright in trees” (Kuhl, 1980). After itemizing and taking pictures of the various misdeeds, he hiked 6 miles to a place called Chain Meadows where the same outfitter kept another camp. The situation there was even worse: “Corral area completely devoid of vegetation. Looks like pig pen. All trees show root exposure…yellow plastic rope and electric insulation nailed to trees, still up” (1980). Kuhl continues:

General impression: complete untidiness, massive ground cover impact, no effort to do any clean up. Complete disregard or care for the campsite and F.S. regulations. After 7 years on the job, it is still one of the worst I’ve seen…(1980)

That was all in a day’s work. The next morning, he continued hiking along Army Mule Trail to check on a different outfitter’s camp. “Another mess,” he writes, “Bits of trash, smashed cans, plastic, scattered all over…horse manure in meadow” (1980).

Back at Moose Creek Ranger Station Kuhl would collect his findings into reports, yet before submitting them he always made the effort to contact the offending outfitter in person or by mail to ask them to clean their mess. It usually worked to the benefit of both parties: drawn-out proceedings and acrimonious relationships with cantankerous outfitters were avoided. Then he’d hit the trail again.

On July 30th Kuhl strode a leisurely 17 miles to Big Rock, an isolated cone-shaped granitic extrusion which he scaled for his own leisure. At Big Rock he cached “over 100 pounds of garbage” (1980) from the surrounding area for pick up at a later date. Kuhl then hiked another 8 miles to Lizard Lakes where he dismantled two recent fire rings left by backpackers. Though most of the entries follow a similar pattern—hike, document and/or remove signs of human activity, hike some more—sometimes Kuhl leaves you with more to ponder. After a night spent at Lower Lizard lake, where a bull moose came within 10 feet of his camp, he “climbed to Lone Lakes via cross country route. Eagle feathers still on top of unnamed peak. Fresh goat tracks ahead of us but none seen” (1980).

The wilderness is a hungry place where things like exposed feathers are unlikely to remain in place for very long, let alone on a windswept peak. This fact, combined with their prominent position atop the peak, suggests deliberate placement. Yet despite what appears to be human intent and, by extension, presence, in the placement of those feathers, Kuhl doesn’t speculate about who may have put them on the unnamed peak or when. Nor does he consider removing them despite the unnatural duration, even permanence, of “still.”

According to the Wilderness Act of 1964, human presence is defined by the “imprint of man’s work” in the form of “permanent improvements” that distinguish humans from nature and that must remain “substantially unnoticeable” in designated Wilderness areas. As an imprint of human presence, the eagle feathers are an anomaly in the ranger’s extensive catalogue of imprints (trash, plastics, cigarette butts, undemolished fire rings, beer cans, electric wire…etc.) deemed unfit for a wilderness ethic. The feathers are not human-made, yet they remain noticeable as a trace of human presence in Wilderness, one whose tracing by Kuhl gently resists the human-Wilderness binary that the notebooks officially enact.

The feathers illustrate how human presence cannot be reduced to man-made objects or improvements. Whether intended or not, the feathers gesture toward an understanding of Wilderness that isn’t predicated on setting humans and nature apart. Given the importance of eagle feathers to Indigenous populations who have called the Selway-Bitterroot home for thousands of years, the feathers represent different traditions of human habitation and conceptions of presence that lie beyond Wilderness jurisdiction. And as eagle feathers placed on an unnamed peak show, these traditions persist despite efforts aimed at their erasure.

References:

COMPLETE TEXT OF THE WILDERNESS ACT

MG 453 Moose Creek Ranger District Historical Files, 1893-1995