Post written by Marwa Elsayed, recipient of the 2025 Gary E. and Carolyn J. Strong Special Collections Fellowship.

When I first saw the announcement for the Strong Fellowship, I was curious and unsure of what to expect. I read about it in the University of Idaho’s Daily Register email and thought it sounded like a meaningful way to spend my summer, something different, and a chance to do hands-on work outside my usual research bubble. The idea of preserving history and making archival collections more visible and accessible to others appealed to me. I liked that it was about bringing out stories that might otherwise stay buried in boxes, and I wanted to contribute to that mission.

Part of the reason I was drawn to the Kenneth Hungerford materials in the Wildlife Resources Department Records collection is that natural resource study in Idaho is entirely unlike what I knew growing up. As an international student from Egypt, a country with no forests, the concept of managing wild forested landscapes was completely foreign to me. I have some sense of how wildlife and forestry are studied today from conversations with friends in this field, however, discovering how this work was done in the past long before computers or even standard lab equipment was something I was excited to learn about.

My background in research and public administration helped; I’m used to sorting through primary sources, creating systematic records, and keeping track of metadata. But exploring this collection gave me a very different perspective on conservation, and I hoped it would broaden the way I approach my own work.

The main goal of my fellowship was to work through the boxes in the Hungerford collection, sorting, organizing, rehousing, and describing each set of materials, all while building the metadata needed for the collection’s finding aid. My days usually started with opening a box and seeing what was inside: sometimes neatly labeled folders, sometimes loose papers and handwritten notes, sometimes glass negatives wrapped in decades-old sleeves. I’d check the contents, take notes, and carefully rehouse items as I went along.

There was definitely a learning curve. In the beginning, I found myself writing down every detail, unsure of what would matter later. Over time, I started to recognize patterns, what information was important, what showed up over and over, what was unique. Some challenges were practical: items without titles, stray notes, or mixed administrative files. But each puzzle was also a lesson. I was lucky to have strong support from my mentor, Rebecca Hastings, who answered my endless questions and offered guidance when things got confusing.

Archival work on this collection often meant carefully handling fragile glass negatives, trying to decipher a scientist’s hurried old field notes, or re-sorting a box that turned out to be out of order. The hands-on work was sometimes tedious, sometimes surprising, but always rewarding! The most memorable moments for me were finding hand-drawn graphs and field maps, realizing that someone had carried these into the woods and recorded data on the spot. It made me pause, a quiet recognition of the person behind the materials and the care embedded in the work.

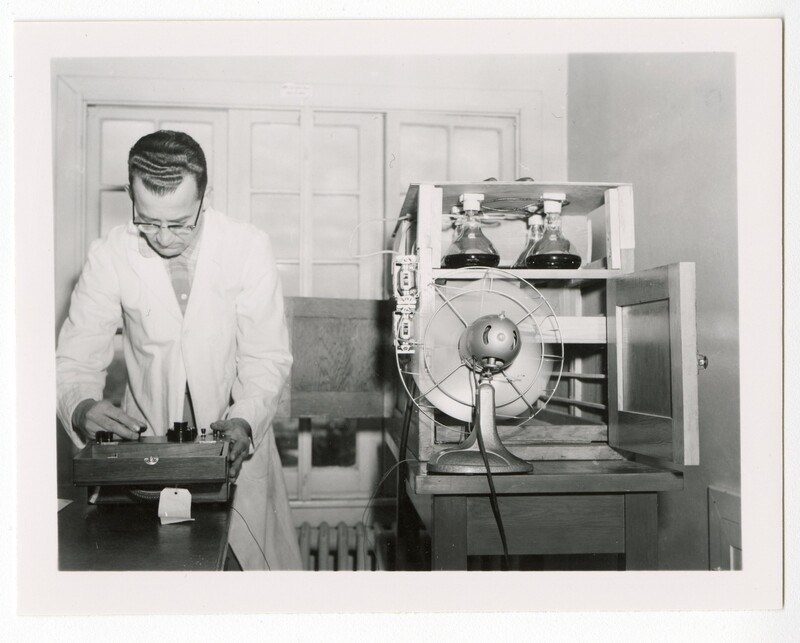

The collection also included detailed maps and aerial photos, photo prints from research sites, and pages of species observations and experimental results. I found vegetation classifications, technical diagrams, seedling studies, research proposals, conference papers, bibliographies, published articles and reprints, and course materials like assignments and readings from classes Hungerford taught. There were also stacks of graduate student records and graduate theses from the 1950s to the 1970s, as well as range ecology studies, rodent behavior experiments, and administrative paperwork!

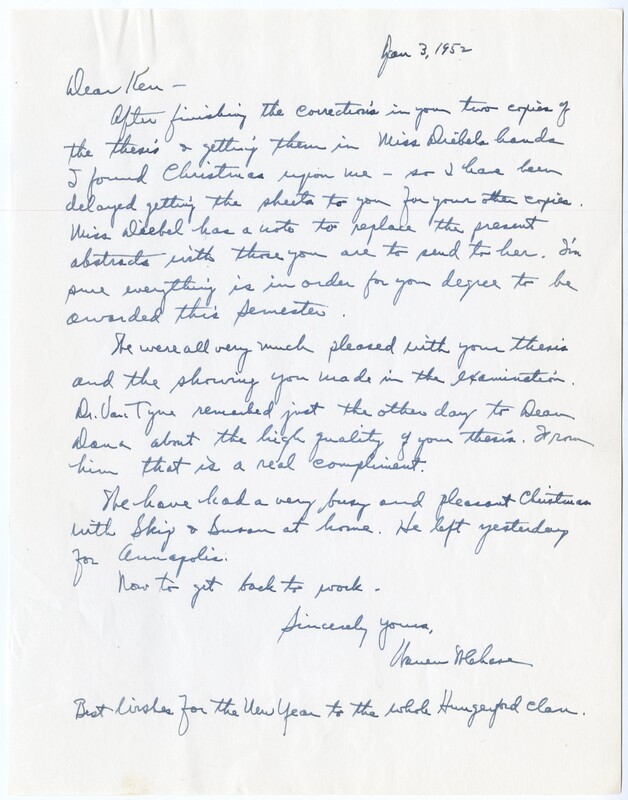

Another type of item I found compelling was correspondence. Reading them felt so engaging. One example is a January 1952 letter, shown above, to Kenneth Hungerford, congratulating him on his thesis and sharing brief holiday news.

Reading other correspondence in the collection; you get drawn into the back and forth: negotiations for grant money, discussions about research sites, updates from graduate students, or even whether a student would get a spot in the program. The letters revealed a certain etiquette and formality in how people wrote, and also a sense of community and connection that still holds up today. You see how much scientific work, then and now, depends on collaboration and sometimes just persistence.

This fellowship pushed me to grow as a researcher and to learn the practical aspects of archival work. There is a kind of attention to detail and a sense of memory in those old notes that is hard to replicate in today’s digital formats like spreadsheets or data files. At the same time, working to preserve and organize these materials showed me how much is gained when we make the past accessible to new eyes.

I am grateful for the opportunity and all the support I received this summer at Special Collections and Archives, especially from my mentor and from Dulce and everyone in the office. The atmosphere was always welcoming, and it was inspiring to see other students and staff dedicated to connecting people with history. This experience made me realize that archives are about making the past matter for the future.