The Marylyn Cork Priest River Historical Collection is the culmination of forty years of incubation. The origins of the physical collections were first developed in the 1980s by Richard Gregory with support from the Idaho Humanities Council. These efforts were expanded by local historian and writer Marylyn Cork, creating nearly 1,800 historic photographs that document the timber industry, community life and cultural heritage of the Priest River area. Fast forward to 2024, when Christa Shanaman of the Priest River Library received funding from the Idaho Humanities Council to digitize this collection, partnering with then U of I Digital Scholarship Librarian and Community Liaison Julia Stone to create this digital repository.

One of the many unique aspects of this collection is the amount of community input that Cork recorded for each of the photos. Many of these images contain extensive lists of people identified by community members. When I took on the project after Julia Stone left for Portland State University, one challenge that I needed to figure out was how to retain all of this important, hyper-specific regional detail and still make the collection intuitive for users who had never even heard of Priest River. Every digital collections project is an attempt to balance discoverability and user comprehension while still retaining the identity of the source material.

We ultimately decided to retain the photograph titles penned by Cork, which could be quite informal (“Jam ; Another Jam ; River Jam ; Faded Jam”), as well as preserving Cork’s original notes written on the back of photos as the original description field (“Names typed on back of photo: Front row; left to right: Freddie Saloman, Lloyd Stewart; Carolyn Rose…”) in addition to a more user friendly basic description that a patron can scan quickly to understand the image in front of them (“Three rows of children pose with their teacher in front of a brick building.”). We also wanted to retain the original subject system Cork used to organize the physical collection held at the Priest River Library (“wildlife”) in a separate category to our subject field, which pulls from the Getty Art and Architecture vocabulary, ensuring patrons can search across larger archival databases (“wildlife; deer; Cervidae (family)”).

Digital Projects Manager Maryelizabeth Koepele put a huge amount of work into building out these subject fields as well as identifying locations in the historical photos. Implementing some approaches from my Digital Geolocation Tools for Archival Research Workshop and utilizing historic newspaper resources, we were able to enrich the geographical metadata to provide greater context to how these records related to one another environmentally.

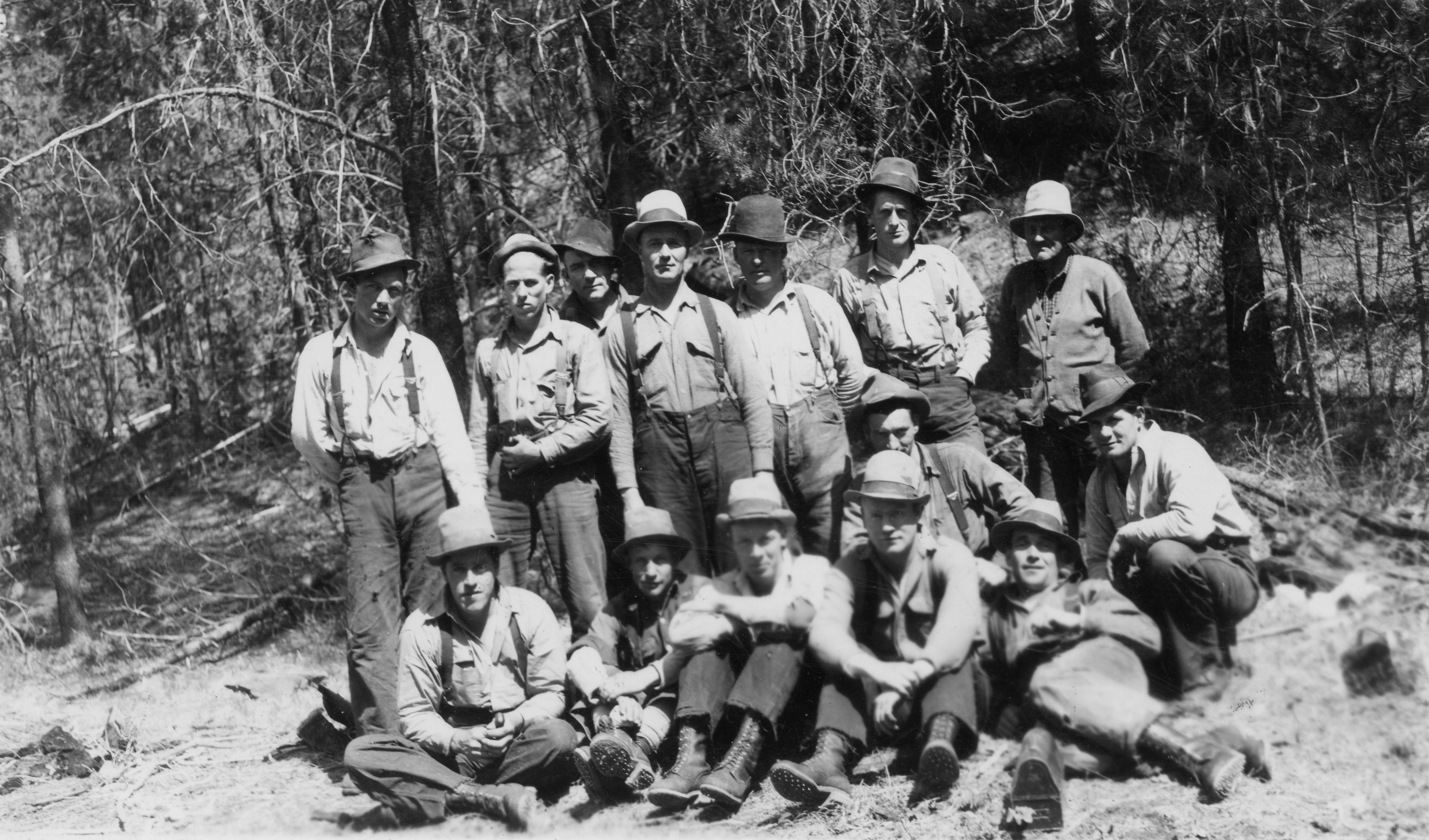

Another unique aspect to this collection are the candid, bystander perspective photographs of logging in the early 1900s. In the historical record of labor, there’s always a vacuum of this type of material. This might be due to manual labor unfairly never seeming important enough to be documented, as well as the vulnerability of these scrapbooks of working class people and itinerant workers.

All that to say, the records of log drives from a worker’s perspective are phenomenal. In an era of incredibly dangerous professions in mining and on the railroad, logging remains the one with the highest fatality rate per worker . The bygone practice of “log booming” or manually guiding logs down a river, was even more prone to injury.

“River pigs” as they were called, used long hooked and spiked tools called “peaveys” and “cant hooks” to guide the timber and for balance, also utilizing spiked boots to grip the wood. A single misstep could send a worker on a drive into the river and between many tons of timber, where they could be crushed.

Because of the danger of these booms, as well as the depletion of lumber in the Priest River area, these drives became more infrequent, concluding with a final boom in Priest River in 1949 and the final drive Idaho on the Clearwater River in 1971. This preceded several laws such as the Idaho Forest Practices Act and the Endangered Species Act, which would alter the timber industry in America drastically, as well as regions like Priest River whose livelihood centered around the industry.

The collection not only reflects the formation and advancement of Priest River in the early 1900s, but also the recession of the timber industry and how the area struggled to retain its identity throughout this economic sea change. As Christa Shanaman describes Priest River: an “attractive little town with a sense of pride in its history and determination to survive.”