Post written by Marwa Elsayed, recipient of the 2025 Gary E. and Carolyn J. Strong Special Collections Fellowship.

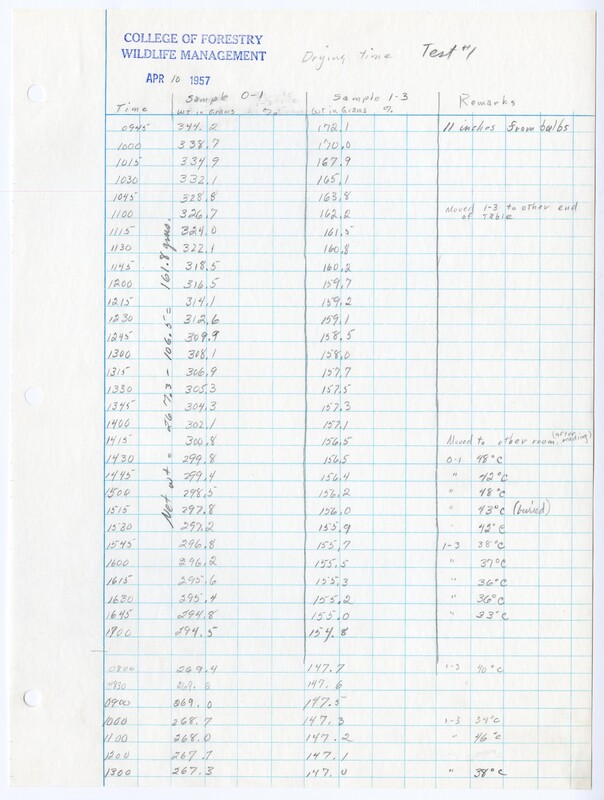

When I first opened the boxes of the Kenneth E. Hungerford Collection (UG 183, Wildlife Resources Department records), I was struck by the sheer physicality of the science inside. Spanning from 1925 to 1986, decades before Excel spreadsheets, data analysis software, or cloud storage, everything was recorded by hand; field notes, correspondence, and detailed data logs written in careful script on yellowing papers. What seems simple now was once an act of great effort and persistence. Through this, you glimpse decades of Idaho’s rich environmental legacy.

This collection documents the progress of wildlife research and education at the University of Idaho across much of the twentieth century. It covers topics like forest disease, upland game birds, and rodent ecology, offering a close look at how wildlife science developed in Idaho and the Pacific Northwest. These records, now preserved in the collection, reflect a great hands-on era of science.

Who Was Kenneth E. Hungerford?

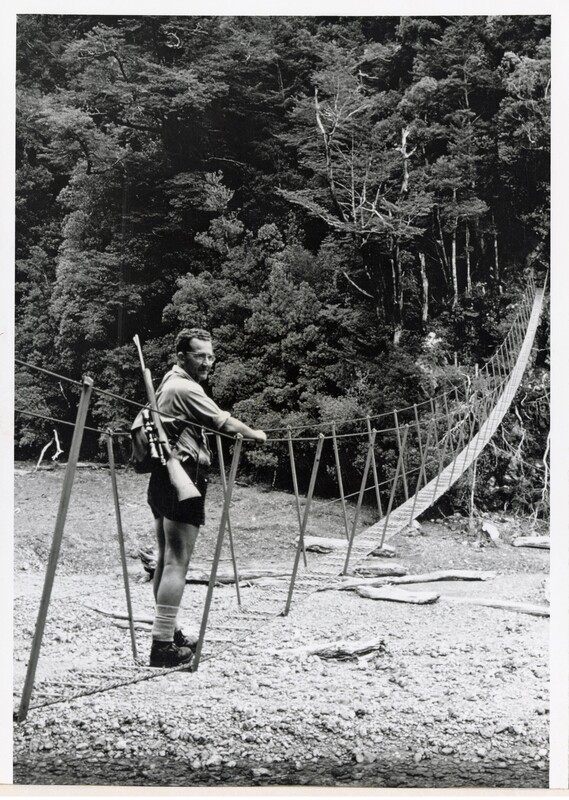

Kenneth Hungerford was a central figure in Idaho’s wildlife research community for over 50 years. Born in 1916 in Madison, Wisconsin, he spent most of his career at the University of Idaho, teaching and conducting fieldwork from 1946 to 1978.

Working on tracking grouse, rodents, and forest pathology across Idaho’s backcountry. Hungerford also worked internationally, advising on environmental issues in Taiwan and New Zealand, and China. While back home he collaborated with agencies and mentored students. He held leadership roles, served on university and civic committees, and stayed active in professional and local organizations. His legacy reflects his curiosity and collaboration, evident in both the forest and the archive.

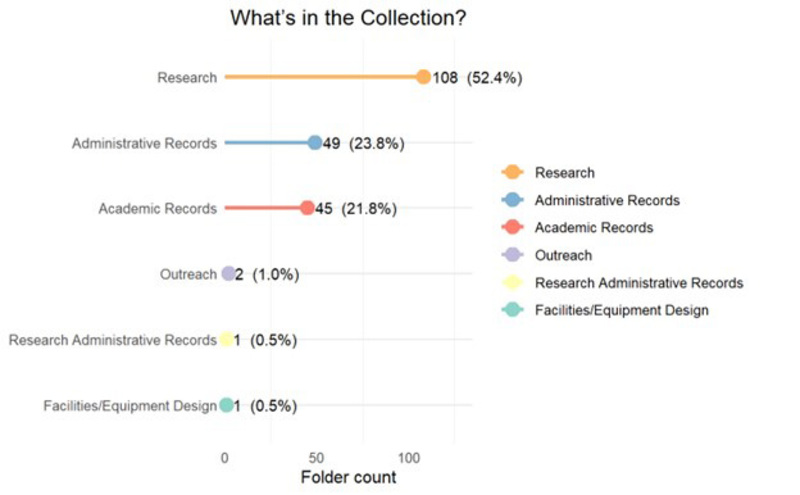

Collection Breakdown by Category

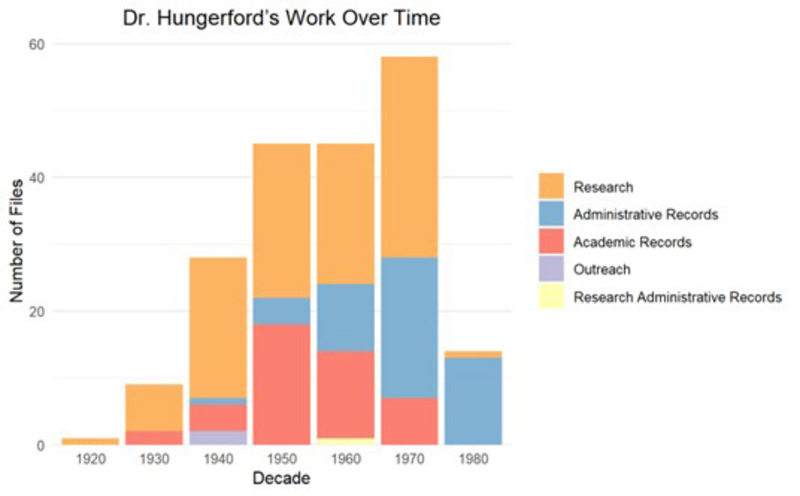

This chart gives a snapshot of what’s in Dr. Hungerford’s collection. Most of the materials are research files, with a significant portion related to administrative and academic work. Smaller categories like outreach and equipment design show us the broader scope of his professional involvement.

Timeline through the Collection

We can see that most surviving material documents field and lab research. Administrative paperwork expands when the department grows in the 1960‑70 s. Teaching and academic records track alongside but never exceed research. After 1978 retirement, production drops as expected; what mostly remained is work related to the University of Idaho Retirees Association board that Dr. Hungerford was involved in.

Stories from the Archive

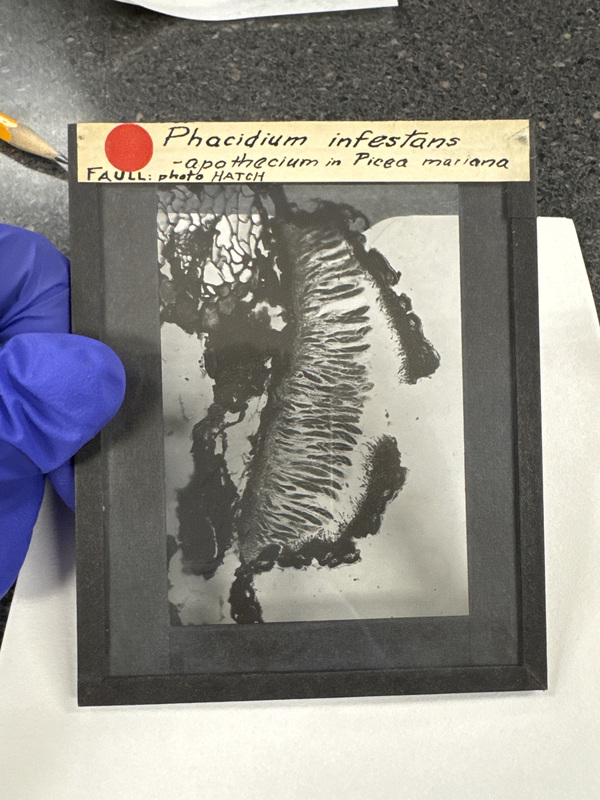

Among the most fragile and fascinating parts of the collection are boxes of glass negatives, delicate photographic plates that captured forest pathology and wildlife scenes in detail. These images, many nearly a century old, offer a window into the techniques and field conditions of early forest science in Idaho.

Beyond visual records, the collection is rich with correspondence like letters exchanged between faculty, funding agencies, graduate students, and research partners and interdepartmental memos and notes. It shows the administrative and logistical side of wildlife research and the professional etiquette and social dynamics of twentieth century science. The letters often discuss fieldwork plans, requests for equipment, and progress updates, but they also reflect the subtle negotiations and formalities that shaped academic and research relationships at the time. Taken together, I consider it a nuanced glimpse into the collaborative networks and everyday realities of building a scientific community in Idaho and the PNW.

Explore and Connect!

Every box, folder, and photograph in this collection now stands as a resource for anyone interested in Idaho’s wildlife history, forest management, or the history of science itself. If you are curious about Idaho’s natural history or the evolution of wildlife science, I encourage you to visit the University of Idaho Special Collections. These records are here to be used, questioned, and built upon!