In the west foyer of the College of Natural Resources building stands an interesting figure: no mere dead tree, it is formally known as “the Snag.” The Snag is a 40-foot whitebark pine that died at some point long before it was harvested and brought to the University of Idaho in 1970. In the mid-20th century, the College of Forestry began outgrowing its space in Morrill Hall, necessitating the construction of a new building, to be completed in 1971. Per a 1985 article by James R. Fazio, then Professor and Associate Dean of the College of Forestry, Wildlife, and Range Sciences, a snag held appeal as a centerpiece for the new building’s main entrance because “it would be long-lasting, maintenance-free, and appropriate” – relevant to forestry but in no danger of growing through the roof (Fazio, 121).

“Gray and weatherbeaten, limbs twisted and complete with bright green moss and woodpecker holes, the ancient white bark pine truly had character.” (Snag Escapes!, 2)

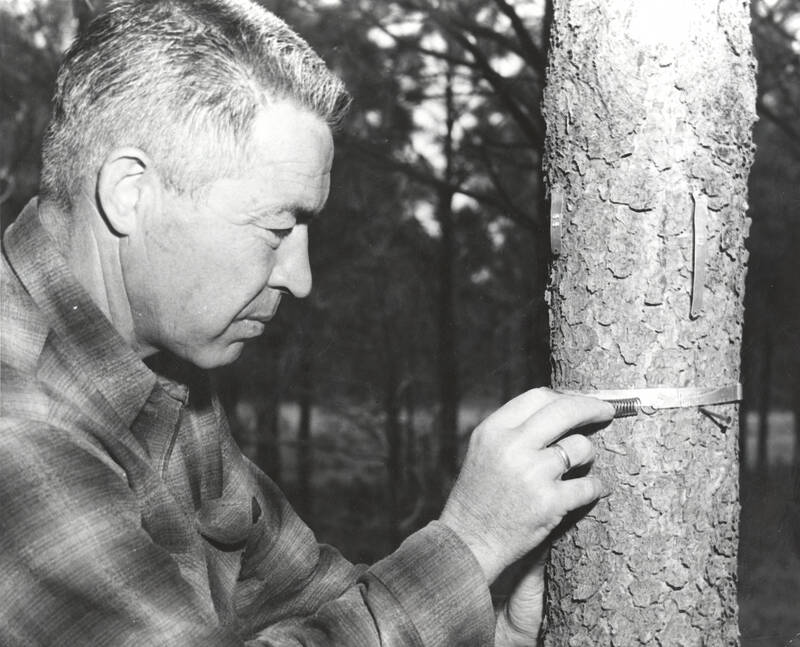

During the summer of 1970, University of Idaho employee Franklin H. “Pit” Pitkin, then manager of the university’s Forest Nursery, helped lead the search for the ideal snag (“Nursery History”). After months of scouring the hills of northern Idaho, the search team discovered “a weathered old giant that had all the right features” at 6,000 feet along Freezeout Ridge, near Mark’s Butte, about 12 miles east of Clarkia (Fazio, 121; Snag Escapes!, 2).

To remove the Snag, the retrieval team cut a short road into the hillside, creating a path for a logging truck. Secured in chains padded with canvas, the Snag was cut at its base and laid carefully on a bed of smaller logs and additional padding in the back of the logging truck. Fazio wrote that this was a “delicate operation” that required the expertise and effort of a team of men, whom he made a point of acknowledging individually, as far as his memory permitted: Pitkin, Dick Bingham, Bud Reggear and his son Bob Reggear, Alex Irby, and Harold West, among others. The Reggears drove the Snag from Freezeout Ridge to Moscow, drawing stares and comments along the way (Fazio, 121-122).

After scraping out the Snag’s rotten core, workers used a crane to lower it into the new building. They then secured the Snag in place by partially filling its center with cement and then inserting steel rods that were sunk 10 feet into the building’s foundation. Following the Snag’s installation, building construction proceeded around it. (Fazio, 122-123; Snag Escapes!, 2).

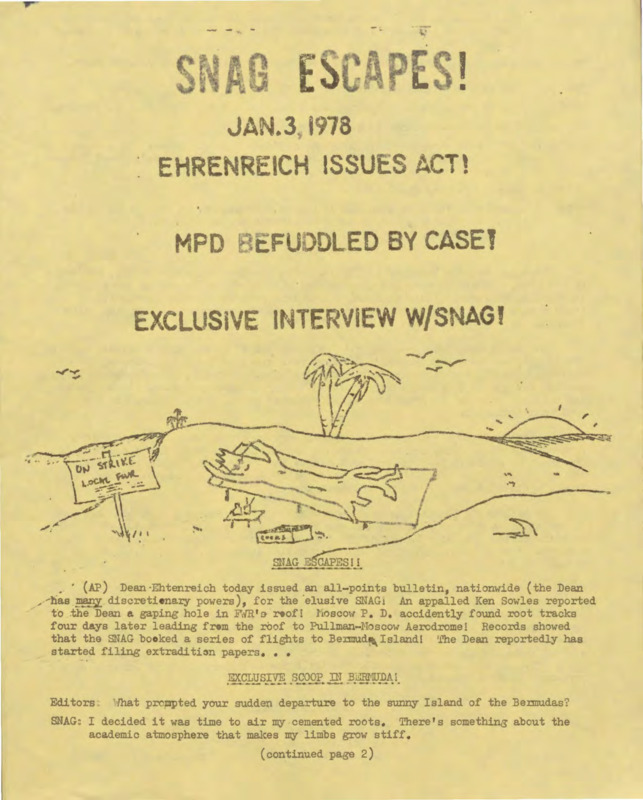

Since 1970, the Snag has appeared occasionally in university records and publications. In 1978, College of Forestry, Wildlife, and Range Sciences Dean John H. Ehrenreich produced a joke bulletin entitled “Snag Escapes!,” in which it is discovered that the Snag has broken away from its steel rods, smashed through the roof of the building, and fled to Bermuda. In an interview conducted while the Snag sunned itself on a beach with a case of Coors nearby, it explains that “it was time to air my cemented roots. There’s something about the academic atmosphere that makes my limbs grow stiff” (Snag Escapes!, 1). Its demands included fire insurance, a pension plan, and that the Dean “stop filing for my extradition” (Snag Escapes!, 2).

In the early 1970s, the students of the College of Forestry, Wildlife, and Range Sciences started The Snag newsletter, published irregularly several times per year until around 2005. The Snag included news from the college, reports on club activities, op-eds by students and faculty, informal scholarship, advertisements for college events, and much more. Early issues, evidently photocopied for distribution, featured hand-drawn depictions of the Snag and other art; the appearance of the newsletter became more standardized and university-branded in later years, but it nevertheless still acted as a medium where students could publicize their work and thoughts.

Fourteen years after the Snag was installed in the College of Natural Resources building, Fazio visited the site on Freezeout Ridge from which the Snag had been removed, an occasion for reflection on what the Snag meant to him: “I felt grateful for the foresight and determination of Frank Pitkin and the many others who gave us the snag. They gave us far more than a decoration, for their gift was a bit of nature’s eternal cycle frozen in time and made part of our lives” (Fazio, 123).

Interested in the history of the College of Natural Resources? Special Collections and Archives has several collections of its records, including our main College of Natural Resources collection, which spans the years 1886 to 2017; the University of Idaho College of Natural Resources Vertical File, which includes materials from 1973 to 2022; and a collection of materials related to the journal Women in Natural Resources. You may visit these materials in person by making an appointment with Special Collections and Archives or view selected digitized materials in Digital Collections’ College of Natural Resources Collection and Women in Natural Resources collection.

Sources

Fazio, James R. “Story of the Snag.” In 1959: The First Fifty Years.

“Nursery History.” Center for Forest Nursery and Seedling Research.

![Snag being removed and transported. [161-7a]](https://objects.lib.uidaho.edu/harvester/small/pg1_161-07a_sm.jpg)

![Snag being removed and transported. [161-7b]](https://objects.lib.uidaho.edu/harvester/small/pg1_161-07b_sm.jpg)

![Snag being removed and transported. [161-7c]](https://objects.lib.uidaho.edu/harvester/small/pg1_161-07c_sm.jpg)